The Codrington Estates

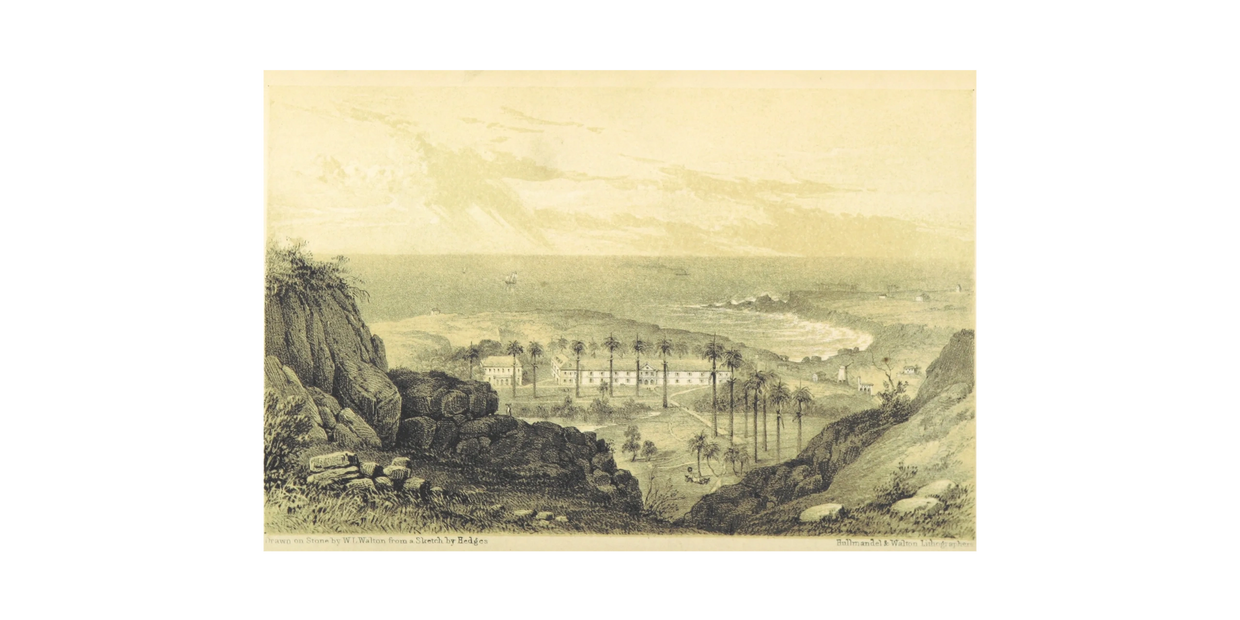

The Codrington Estates, consisting of two plantations in Barbados, were bequeathed to the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel (SPG) by Christopher Codrington upon his death in 1710. Codrington's will specified that these estates should be used not only for the economic benefit of the SPG but also as a site where the enslaved population could receive Christian education. His intention was to keep at least 300 enslaved Africans on these plantations and to establish an educational institution that would provide both spiritual and practical training. This vision marked a unique intersection between missionary work and plantation economics, as the SPG sought to use the estates’ profits to fund their broader missions across the British colonies while also attempting to influence the lives of the enslaved people on the estates through religious instruction. The SPG maintained and operated the two plantations throughout the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries through periods of upheaval and profitability. In that period, they came to own more than 1,400 people of African descent as they attempted to develop a mission focused on enslaved people.

The SPG’s acquisition of the Codrington Estates presented both an opportunity and a theological challenge. While the estates promised a steady source of funding, they forced the Society to confront the moral implications of Christian participation in slavery. Initially, SPG leaders like William Fleetwood argued for the conversion of enslaved Africans, positioning Christianity as a civilizing force that could "humanize" them in the eyes of white Europeans. Fleetwood, in particular, used sermons to address planters' fears that converting enslaved Africans would lead to demands for freedom, instead claiming that Christianity would enhance obedience and docility. Thus, the SPG’s strategy involved framing the conversion as a process that would both uplift the enslaved spiritually and reinforce the existing social hierarchy.

Over time, however, the SPG's approach evolved from a focus on conversion to an emphasis on "civilization" as a prerequisite for religious instruction. Anglican leaders in the SPG and its associate organizations began advocating for a civilizing mission, arguing that enslaved people had to adopt European customs and values before they could be considered candidates for Christian conversion. Figures such as Bishop Martin Benson claimed that enslaved Africans needed to be "made men before they could be made Christians." This shift reflected the Society's adaptation to the prevailing racial attitudes of colonial planters, who increasingly viewed Africans as inherently inferior and in need of reform before they could participate in religious life.

By establishing Codrington College on the estates, the SPG intended to create a model of Anglicanism that could simultaneously serve the colonial order and promote their religious ideals. Codrington College would eventually train clergymen and other officials, helping to entrench Anglican values in the region. Despite the initial humanitarian rhetoric, the SPG’s involvement in the Codrington Estates underscored the complex entanglement of religion, imperialism, and slavery. The College became an instrument of both the British Empire's spiritual outreach and its economic interests, with the enslaved population positioned at the intersection of these forces, subject to both exploitation and the SPG’s conditional offer of religious "uplift."

This shift from a humanitarian to a civilizing mission exemplified the ideological compromise the SPG made to maintain support from colonial slaveholders while attempting to retain its religious mission. As the SPG adapted to the realities of colonial life and the demands of slaveowners, the mission to convert enslaved Africans became increasingly conditional on their conformity to British standards, revealing the complex and often contradictory nature of religious outreach efforts within the institution of Atlantic slavery.

The Codrington Estates continued to serve as a critical site for attempts at Christianizing and educating enslaved Africans. The SPG faced persistent challenges in these efforts, not only from white slaveholders but also from the enslaved people themselves. Many white Barbadians, including the Codrington overseers, resisted religious instruction for enslaved people, fearing it would erode the social order by reducing the distinct line between white owners and Black laborers. To further complicate matters, the belief that baptism would lead to emancipation persisted, creating resistance among slaveholders who worried that religious instruction might disrupt plantation labor and encourage aspirations for freedom among the enslaved.

Turnover among catechists was high on the Codrington Estates, which further hindered religious efforts. Many catechists either died soon after arrival, abandoned their posts, or held condescending views that rendered their attempts at teaching ineffective. These catechists faced several obstacles: a lack of consistent support from plantation management, the exhausting labor schedules of enslaved people, and the widespread perception of African “brutishness” or inability to comprehend Christian teachings. By the 1750s, catechists began to approach the religious instruction of enslaved people with significantly lowered expectations, a shift reflecting the racial biases of the time. This belief that African people were innately inferior, resistant to change, and incapable of deep religious comprehension became a self-fulfilling prophecy, impacting the engagement of both catechists and the enslaved.

The SPG and affiliated groups like the Associates of Dr. Bray introduced various attempts to educate enslaved children on the Codrington Estates and across the Caribbean. However, these efforts often stalled as catechists and educators struggled against entrenched opposition from white plantation owners who viewed teaching reading and Christianity as subversive. The reluctance to spare labor time for education, coupled with the desire of the enslaved to prioritize personal activities during their limited free time, limited the impact of these educational missions. For instance, attempts to enforce regular attendance at catechism sessions were met with indifference or resistance, as many enslaved people preferred to use their Sundays for rest, personal trading, or attending to family matters.

Catechists like Thomas Wilkie, appointed in 1726 after a ten-year vacancy, reported the difficult realities of trying to educate enslaved children who were reluctant to attend religious instruction, often hiding when he approached. Wilkie sought support from the plantation managers to enforce attendance, yet his efforts proved ineffective. The SPG’s position on the estates also reinforced the plantation economy: catechists frequently expressed frustration at being unable to spare enslaved children from labor to attend school, with plantation managers prioritizing economic productivity over religious instruction.

Religious education for the enslaved on Codrington remained inconsistent and limited in scope. The high death rate and shortfall in the enslaved population on the estates intensified the workload for those who remained, leaving little time or energy for participation in religious life. Though some catechists succeeded in baptizing and educating a small number of the enslaved, the larger SPG mission to Christianize enslaved Africans on the Codrington Estates often struggled due to systemic resistance, both from the brutalities of plantation labor and the strong, culturally rooted objections of the slaveholding class in Barbados.

The SPG’s efforts to promote Christian conversion on the Codrington Estates met significant resistance from both enslaved people and plantation managers, largely due to differing perceptions of marriage and sexuality. Anglican missionaries promoted monogamous marriage as part of their religious mission, seeing it as a civilizing force meant to reform the perceived “promiscuous” behavior among enslaved Africans. Many enslaved people, however, came from West African backgrounds where polygamy was common and held cultural significance, making monogamous marriage less appealing. This resistance to Anglican marriage, often perceived by white missionaries as evidence of "African promiscuity," clashed with the rigid structure of Christian monogamy, challenging the missionaries' efforts to “civilize” through marriage.

Missionaries on the Codrington Estates were also challenged by the apathy of white slaveholders who saw little value in regulating the marital or sexual lives of their enslaved laborers. White planters often allowed polygamy and even encouraged multiple partnerships among enslaved people as a means to increase their population naturally. Records indicate that enslaved people on the Codrington Estates and elsewhere in Barbados had a significant amount of autonomy in their relationships, a dynamic that was tolerated as long as it aligned with economic interests, particularly the goal of increasing the labor force through childbirth.

The baptismal records reveal that while baptism among the enslaved population was uncommon, free people of color and mixed-race people were more likely to participate in this sacrament, often using it as a means of social elevation. The distinctions in baptism rates and marriage participation became markers of racial and social stratification within the enslaved population and the free Black community. Baptism offered an avenue for some people, especially free or mixed-race people, to assimilate into the white Christian community, albeit with limitations. On the Codrington Estates, catechists and chaplains occasionally succeeded in converting some enslaved people, but the lack of sustained support and the logistical challenges, such as high catechist turnover and limited instructional time, hindered consistent religious influence.

Ultimately, the SPG’s attempts to enforce Anglican ideals on marriage and family structure were largely unsuccessful on the Codrington Estates, where cultural and economic imperatives took precedence over religious ones. Enslaved people often avoided official marriage and sometimes baptism, as these sacraments could limit their relationship choices or fail to provide meaningful change in their status. Planters, on the other hand, prioritized the economic benefits of unregulated relationships, viewing enslaved people less as potential Christians and more as assets within the plantation economy. This dynamic underscored the broader racial hierarchy that persisted on the Codrington Estates and within the Barbadian society at large, where religious rites like baptism and marriage served as tools of social distinction rather than universal practices.

In June 1738, a significant labor protest occurred on the Codrington Estates when enslaved people left the plantations and marched to Bridgetown, the capital of Barbados, to present grievances to Reverend William Johnson, one of the Society's attorneys. The protest was sparked by severe working conditions, inadequate food, clothing, and harsh treatment on the estates. Enslaved laborers reportedly hoped that Johnson, as an Anglican minister, would be receptive to their concerns due to the humanitarian rhetoric the SPG promoted. While the specifics of Johnson's response are unclear, the protest highlights the complex relationship between SPG’s stated Christian values and the brutal reality of plantation life.

The protest underscored the horrific conditions enslaved people faced on the estates. Death rates were high due to overwork, disease, and malnutrition, and the plantations were severely understaffed, with fewer than the 400 enslaved people necessary for full production. While managers were instructed to use less force, they regularly relied on whipping, branding, and even the intercolonial slave trade to control and punish workers. The SPG branded enslaved people with “SOCIETY” to mark ownership, a practice condemned by some SPG officials but initially tolerated to prevent runaways. Such measures exposed the SPG’s moral contradictions, as they continued employing violent tactics typically used by secular slaveholders to ensure productivity.

The protest’s aftermath illustrates how the SPG managed labor unrest. While Vaughton initially promised to address complaints, he ultimately dismissed the demands and reverted to punitive measures. Those who participated in the protest faced severe public whippings in Bridgetown and additional punishments on the plantation, and the two alleged protest leaders were jailed. The SPG’s response reflected its internalized fear of slave insurrection and emphasized the need for control over perceived “subversive” actions among the enslaved. This incident demonstrated how, despite occasional concessions, the SPG prioritized economic outcomes over the welfare of enslaved people, underscoring the stark divergence between the SPG’s ideals and its operational realities.

The labor protest also exposed a shift in the SPG's view of enslaved people and the feasibility of their religious conversion. Following the event, SPG officials increasingly described Africans as inherently “uncivilized” and incapable of accepting Christian teachings. Figures like Rev. Thomas Wharton and Bishop Martin Benson argued that enslaved people needed to be "civilized" before they could embrace Christianity, indicating a new emphasis on racial inferiority as a barrier to religious instruction. This notion of civilizational hierarchy became an integral part of the SPG’s justification for the limited success of their missionary efforts, and the Codrington Estates became emblematic of the ideological conflict between religious aspirations and the economic imperatives of plantation slavery.

In the wake of the protest, the SPG's commitment to Christianizing enslaved people continued to wane. The combination of internal conflict, planter opposition, and slave resistance made the SPG's mission increasingly untenable, leading to their eventual abandonment of widespread slave instruction. The incident marked a pivotal moment in the SPG's approach to missionary work, revealing the limitations of Anglican ideals within the rigid and violent structure of the plantation economy. The protest and its repercussions highlighted the SPG’s ultimate alignment with the brutal realities of colonial slavery, despite its outward claims of humanitarianism.

By the 1820s, amid rising abolitionist pressure, the Codrington Estates in Barbados became a focal point for implementing religious instruction as part of broader "ameliorative" reforms meant to promote Christian virtues among enslaved people. Metropolitan reformers, including Sir George Henry Rose and MP George Canning, advocated for legislation to encourage slaveholders to allow Christian conversion, believing that gradual moral "improvement" of enslaved populations would pave the way toward eventual emancipation. These reforms included Sunday worship, baptism, and marriage among the enslaved population, which were promoted as means to instill loyalty and moral discipline. In response, the SPG and Codrington managers began to enact various enticements, such as offering alternate Saturdays off, to encourage church attendance and adherence to Anglican norms.

One key legislative step was the ban on Sunday markets in Barbados in 1826, effectively mandating Sunday observance and attendance at Anglican services. This policy disrupted established social and economic practices, as enslaved people traditionally used Sundays to trade, socialize, and engage in autonomous economic activities. This legislation, alongside the promotion of religious services, aimed to align Sunday activities with Anglican values. Codrington officials complied by granting the enslaved every alternate Saturday off for market activities, attempting to prevent resentment and maintain productivity while also bolstering church attendance. However, the enslaved often resisted full compliance, showing up late to services or avoiding attendance entirely, indicating that Anglican practices did not resonate deeply within their cultural framework.

Marriage became another focus of ameliorative policies, as the SPG sought to "civilize" enslaved people by encouraging monogamous relationships through Anglican marriage rites. Previously, marriage ceremonies among enslaved people at Codrington were rare, and the cultural resistance, especially among women, was strong. SPG officials, in response, introduced targeted incentives like additional time off for married women, improved housing, and provisions to secure children’s inheritance within marriages. These incentives led to a notable increase in formal marriages on Codrington, with enslaved women reportedly more receptive to Anglican marriage when it conferred tangible benefits like reduced labor and greater autonomy.

The introduction of Anglican marriage and the restriction of cultural practices, such as Sunday markets and polygamy, marked a period of "domesticating" enslaved people according to British norms. On Codrington, religious instruction efforts often targeted enslaved children, who were seen as more pliable and less influenced by African customs. These children attended Sunday schools and were catechized under SPG policies that aimed to integrate religious instruction with basic literacy. Codrington officials built a schoolhouse and mandated attendance, focusing on Christianizing the younger generation in hopes of cultivating a compliant, future labor force more closely aligned with British cultural ideals.

By 1833, the SPG’s ameliorative policies culminated in a unique contractual agreement on the Codrington Estates, wherein nine enslaved families were granted greater autonomy, including permission to lease land and maintain subsistence gardens. The SPG intended this as a model of “gradual manumission” in response to abolitionist criticisms of its plantation holdings. This period marked a significant shift, as religious amelioration was used to soften public criticism while reinforcing the SPG’s economic control over enslaved populations, revealing the complex intersection of religious instruction and economic motives within the Codrington Estates' operations.

The Codrington Estates played a crucial role in the heated debates around emancipation within the Anglican Church in the 1820s and 1830s. By this period, evangelical Anglicans and abolitionists had grown increasingly vocal, criticizing the SPG for holding slaves while simultaneously preaching Christian salvation. Prominent critics like Reverend John Riland and evangelical publications such as the Christian Observer openly questioned the morality of the SPG's reliance on slave labor. These critics argued that the SPG’s claims of benevolent slave ownership were incompatible with Christian principles and accused the Society of perpetuating brutality under the guise of religious instruction. Riland, in particular, lambasted the SPG for failing to educate enslaved people for freedom, instead entrenching them further in slavery through religious practices that reinforced obedience rather than offering true spiritual or social liberation.

In response to mounting public criticism, the SPG began implementing gradual emancipation policies on Codrington, allowing enslaved people to purchase freedom at reduced rates and offering plots of land for semi-autonomous farming. This move was partly strategic, intended to placate abolitionist sentiments and retain control over the labor force under a guise of reform. By 1833, the SPG had negotiated land allotments for nine families on Codrington, a system that allowed these families to grow food for themselves and limited dependence on the estate. This policy continued under the apprenticeship system, providing former slaves with some autonomy while maintaining them as a stable labor source for sugar production.

With the passing of the British Emancipation Act in 1833, the SPG was forced to accept the abolition of slavery, receiving over £8,000 in government compensation for 410 enslaved people freed from Codrington. The SPG continued to employ its former slaves as apprentices until 1838, effectively transitioning them from forced labor to a system of paid wages. However, despite the shift to free labor, the racial and social hierarchies ingrained by decades of SPG policies persisted. The SPG’s legacy in the Atlantic world was one of moral contradiction, as the organization grappled with the complexities of promoting Christian ideals while simultaneously exploiting African labor. This ideological tension continued to shape attitudes within the Anglican Church even after emancipation, influencing future missions in Africa and beyond.

©2021-2026 Matthew Blake Strickland - All Rights Reserved.

This website uses cookies.

We use cookies to analyze website traffic and optimize your website experience. By accepting our use of cookies, your data will be aggregated with all other user data.